Center Stage

The all-but forgotten "might have been" moment when the Apostle Islands almost became center stage for world politics and the United Nations

As I write this, delegates of the UN are meeting halfway around the world in Nice, France, a picturesque city on the southern coast of the French Riviera. They are in the final days of the third UN Ocean Conference, UNOC3. Under the banner of “Our Ocean, Our Future: United for Urgent Action” those delegates are debating, negotiating, and working to finalize a package of voluntary commitments from participating countries aimed at securing the future of the earth’s oceans including their natural and human environments.

At the heart of the debate is the fate of the world’s small islands which lie in the crosshairs of global climate change due to inherent ecological fragility and their vulnerability in the face of dangerously rising sea levels.

Little do those delegates know of the irony at play here, an almost forgotten “what might have been moment” in history when our very own group of small islands in Lake Superior, the Apostles, almost became the center of the world stage as the location for the international headquarters of the United Nations.

In early 1946, a special committee was appointed to research and select a permanent home for the world headquarters of the newly-formed United Nations. In a laborious process, a number of sites across the world were one-by-one considered and then ruled out, whether for astronomical costs or other logistical issues, putting the special committee in a bind with a looming deadline.

In February of that year, Charles Sheridan, then the editor of the Washburn Times, offered some assistance. Penning an open letter in the Ashland Daily Press, Sheridan offered the committee a “solution to your difficulties by seriously and respectfully proposing a much more appropriate site for the UNO home … namely the Apostle Islands off the northern tip of the state of Wisconsin in Lake Superior.”

Perhaps it was a slow news day, or perhaps he was serious, but Sheridan’s letter laid out a compelling rational for choosing the islands, citing the area’s climate, central location, even its cost-effectiveness. While the price tag for acquiring the land in other places ran into the millions, an Apostle Islands location, Sheridan argued “won’t cost you much, if anything. And economy is a factor not to be ignored even by the UNO!”

But for all the economic and objective rhetoric employed by the author, the heart of the proposal pulsed with a more philosophical beat. “With a history going back to the very dawn of time,” he wrote, “the Apostle Islands offer an appropriate location for an organization that seeks to bring the dawn of a new era in the unhappy annals of mankind.”

Although Sheridan’s geology may have been questionable, he argued that the “red sandstone of the Apostle Islands … considered by many geologists to be the oldest land on earth” and the product of “the greatest volcano the world ever knew,” would make a fitting backdrop for the type of deep deliberations asked of UN delegates. “It will be good for the ego of UN delegates to gaze on those beautiful red shorelines and meditate,” he opined. “Such a thought is enough to reduce even the atom bomb to its proper small place in the panorama of earthly time and should be conductive to a recognition of the insignificance of men and their petty affairs and the folly of human conflict.”

Further, Sheridan threw the area’s history into the mix as “a sterling example of friendship and cooperation between men of many origins. Here in peace dwell Americans whose fathers were Indians, French, English, Yankees, Norwegians, Swedes, Poles, Finns, Czechs, Hollanders, and a dozen other nationalities.” Such a melting pot of humanity, he suggested, would inspire among the delegates of the UN, “a healthy atmosphere of democracy and mutual understanding in which the democratic ideals of the United Nations can thrive and grow.”

He even had a spot in mind: Presque Isle on what is now called Stockton Island.

“Presque Isle, 10,000 acres in extent and the second-largest of the archipelago, is owned by the University of Wisconsin,” he wrote, “and there isn’t much doubt that it could be had for nothing for use as a UNO capital. On the other 22 islands of the group there are thousands of acres awaiting development… If you need still more land, or a mainland base,” he continued, “the whole end of the Bayfield peninsula is available.”

“Well, there’s the story,” he concluded, “and I challenge you to find anything seriously wrong with it… You can look the nation over and you won’t find a more typically American area than this one … We don’t have much money or much metropolitan sophistication around here and our pleasures are simple, but we know and practice friendship and harmony, we hate intolerance and discrimination, and we aren’t bored with life or hopeless about the future. Perhaps the UNO delegates could even learn a few things from our way of life. We’re willing.”

He signed it, “Respectfully, Charles M. Sheridan, Editor, The Washburn Times.”

It is not known if Sheridan’s offer of the Apostle Islands and Presque Isle was taken seriously by the committee. Although many other places did receive serious consideration as the location for the UN Headquarters, an offer of an $8.5 million donation from John D. Rockefeller for the purchase of a site in mid-town Manhattan (ironically the site of an old slaughterhouse) sealed the deal. Construction began there on October 24, 1949 and was completed in 1952. With that, the echo of the offer of the Apostle Islands faded into the silence of all-but forgotten history.

It is in that silence that I often drift seeking a bit of peace in these times of such tumultuous political news. Sipping my coffee and thinking of that letter, I can’t say I can find much wrong with the arguments of Charles Sheridan. An organization like the UN, with its motto of “Peace, dignity and equality on a healthy planet,” would do well to look to a place like the Apostle Islands from time to time, a place where perspective is written in the rock of every cliff face and peace can be found in a simple walk along any curve of sandy beach.

Of course, I am glad it didn’t happen for the development and attention it would have brought to this corner of the world. Still, I can’t help but wonder how the world might be different if that letter of Charles Sheridan had swung the eyes of the UN committee in our direction. How might the arc of decisions bend differently if the UN delegates pondered their weighty questions among this constellation of islands?

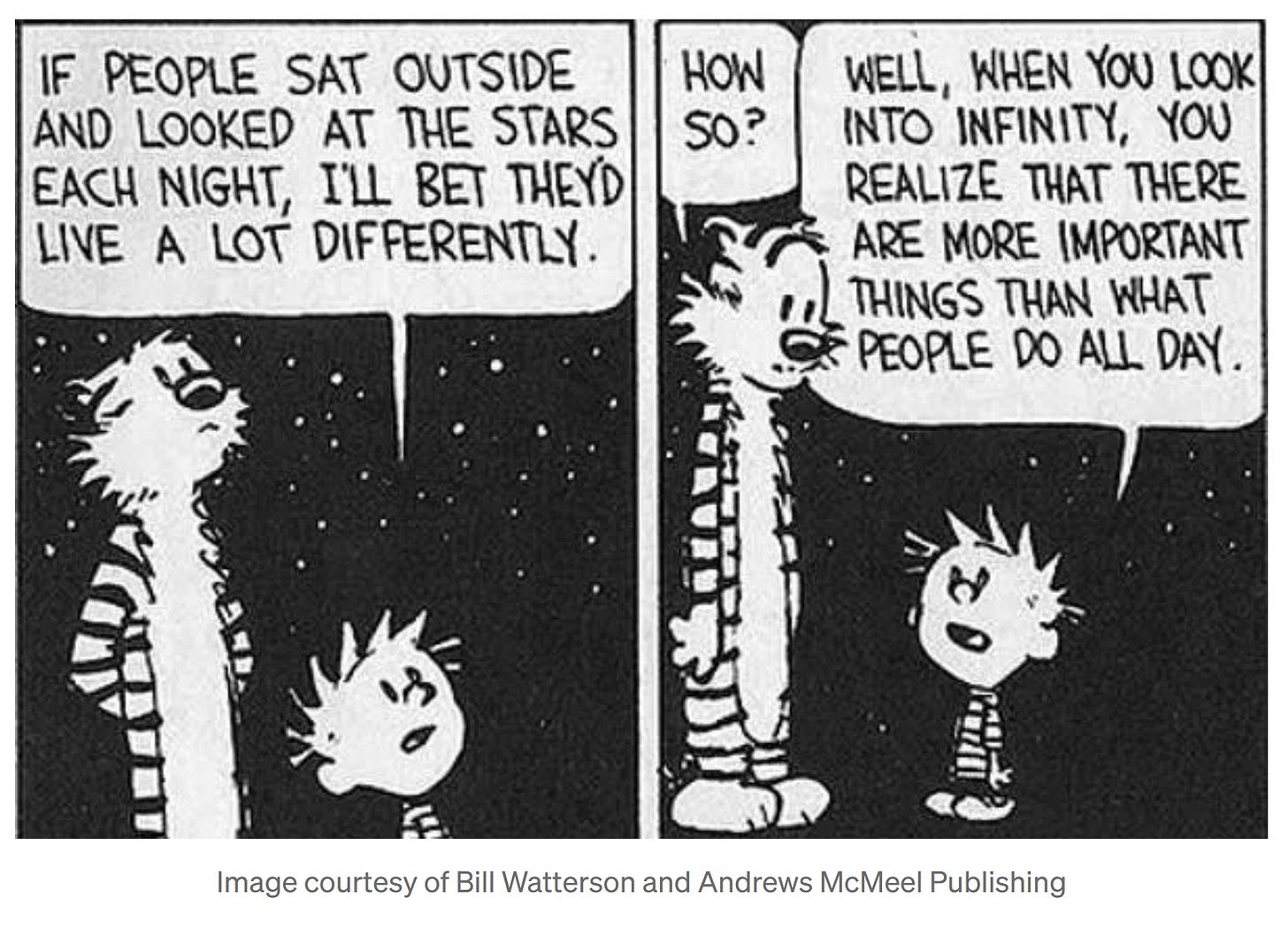

I sip my coffee and remember one of my favorite “Calvin and Hobbes” cartoons.

Oh what might have been, I think to myself on those mornings, savoring one more sip of coffee, one more breath of peace and quiet among the islands before turning back towards home to face whatever chaotic political challenges the new day may send our way.

— Jeff Rennicke (all photography by the author unless otherwise noted).

(Note: I first read about the Charles Sheridan letter in The Lake Superior Country: In History and In Headlines, volume 5 in the Historic Preservation Series by Jared M. Glovsky, published by Paradigm Press, 2002)

This is an amazing story and could not have been better told. Thanks, and I also am glad this did not happen.

Wow - I had no idea. Thanks Jeff!