Does Nature Need Us?

Some journeys are just meant to be shaped like a question.

Straight off the bow of the Little Dipper, silhouetted against the sun just now pillaring through the clouds up the North Channel: a rowboat, the cadence of the oars flashing like wingbeats. I throttle back, both to slacken my wake out of respect for the rower, a friend of mine who shares my love of island mornings on the water, and because my mind is somewhere else, far away on a tiny speck of an island in the Mississippi Gulf. In the silhouette of the boat ahead floats the image of another rowboat, another artist, and a question that has helped shape the origins of my own search for a sense of place among these islands.

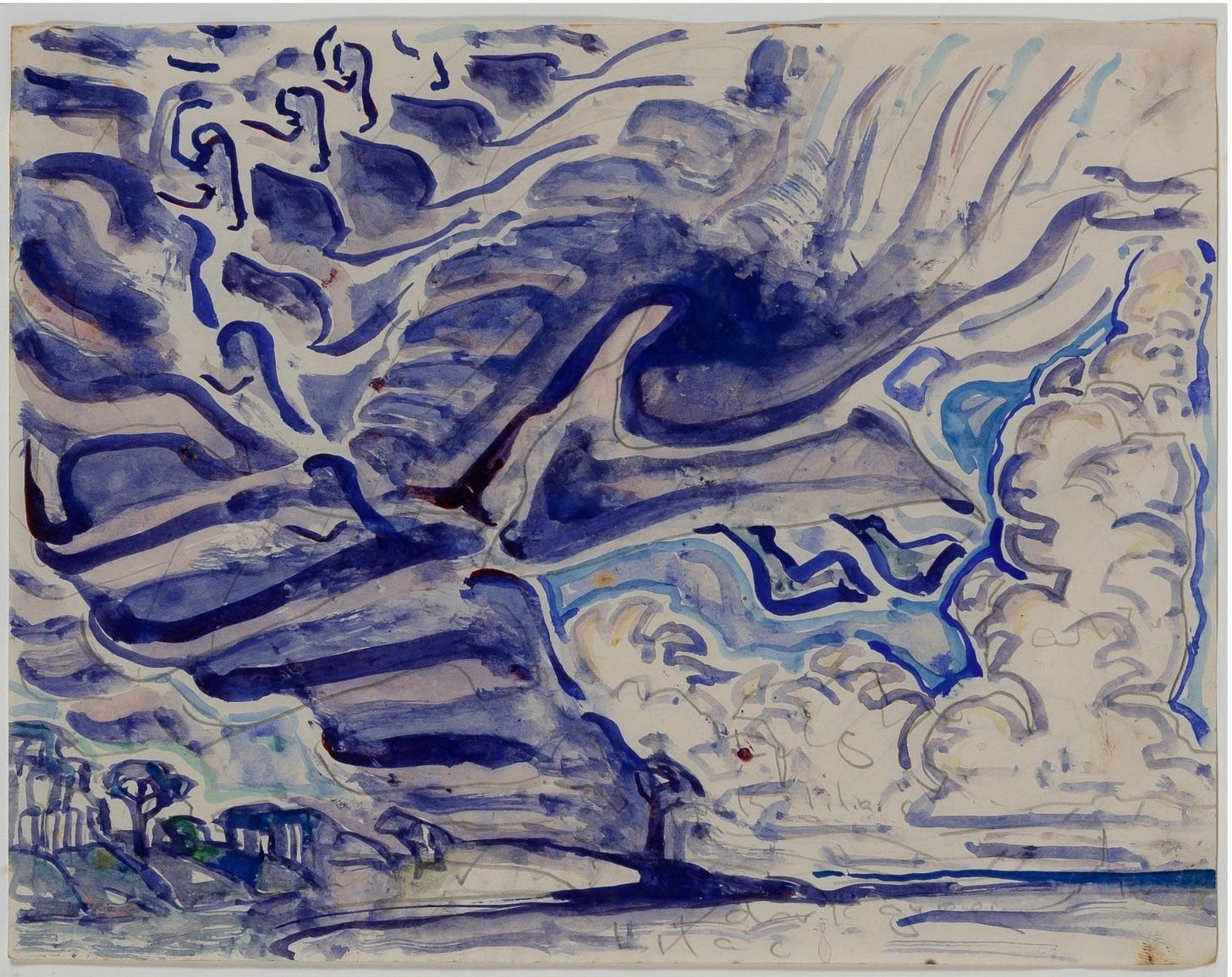

“Self-Portrait while Rowing” (Walter Anderson 1903-1965)

Horn Island is a thin brushstroke of sand and grass, ten miles long, less than a mile wide and barely 20 feet above the high tideline at its peak. It sits twelve miles off-shore of Ocean City, Mississippi and is now a part of the Gulf Islands National Seashore. I’ve often thought that it could easily be slipped in to the constellation of the Apostle Islands and seem right at home. But that is just the beginning of the connections.

In the 1950’s and early 60’s, a prolific, visionary, and fiercely-independent artist named Walter Anderson sought refuge from the world and a deep “realization” of his place in nature on Horn Island. Dubbed the “Hermit of Horn Island,” Anderson could often be seen festooned with a ratty old Fedora silhouetted against the setting sun, rowing his tiny, salvaged rowboat into the gathering darkness, refusing lifts from passing fishermen, taking up to six hours to make the 12 mile crossing to the island.

(Horn Island - Walter Anderson 1903-1965)

Anderson often called his trips to Horn Island “going home” even though he had a “home” complete with a wife and children that he left behind on shore. Once on the island, the artist would enter a state of reverie, pacing the beaches, crawling on his hands and knees through the mud, working feverishly to capture the ever-changing island light in hundred of watercolors. It consumed him, the island light, this contact with nature on his own terms. It was, to him, a “physical craving, like hunger or sex, a necessity, a burning,” as he once said.

Working himself to exhaustion, Anderson created painting after painting on flapping sheets of typing paper — vibrant, frenetic, colorful beachscapes, waves, birdlife, sea creatures, vegetation, nothing escaped his artistic eye and flashing brush strokes — and then scrounge whatever food he could before crawling off to sleep under his overturned boat only to wake and do it all again for weeks at a time.

(paintings by Walter Anderson)

It was, however, not all bursts of color and artistic reverie. Horn Island has its perils — fierce winds, prickly wildlife, swarming insects, scorching heat — and in the course of his almost euphoric episodes, Anderson would be subject to nearly all of them. Once, reaching for a bird nest to get a better view he was bitten by a cottonmouth and was near death when he was rescued by a pair of passing boaters. On his final trip to the island in 1965, Anderson barely survived what became known as Hurricane Betsy (the first $1 billion storm in the U.S.) and even then would not leave despite the pleas of his worried family relayed through the Coast Guard sent to “rescue” him from the storm-ravaged island.

I have long been drawn to the story of Walter Anderson not just for the simplicity of living under an overturned boat, the freedom of pursuing the bursts of creativity unfettered by the outside world, but for his unique and thought-provoking vision of the role of an artist in the natural world. “Order is here,” he said of his wilderness island, “but it needs realizing.” Nature, in Anderson’s view, was somehow incomplete without an artist to “realize” it. Only an artist like him could, in his view, fully “realize” nature which “… needs only to be observed and appreciated.” Further, he believed that the natural world, as incomplete as it is, was “only too glad to have assistance in establishing order.” Belief that it was his duty to establish that order as an artist is exactly what drove Walter Anderson to such life-threatening extremes.

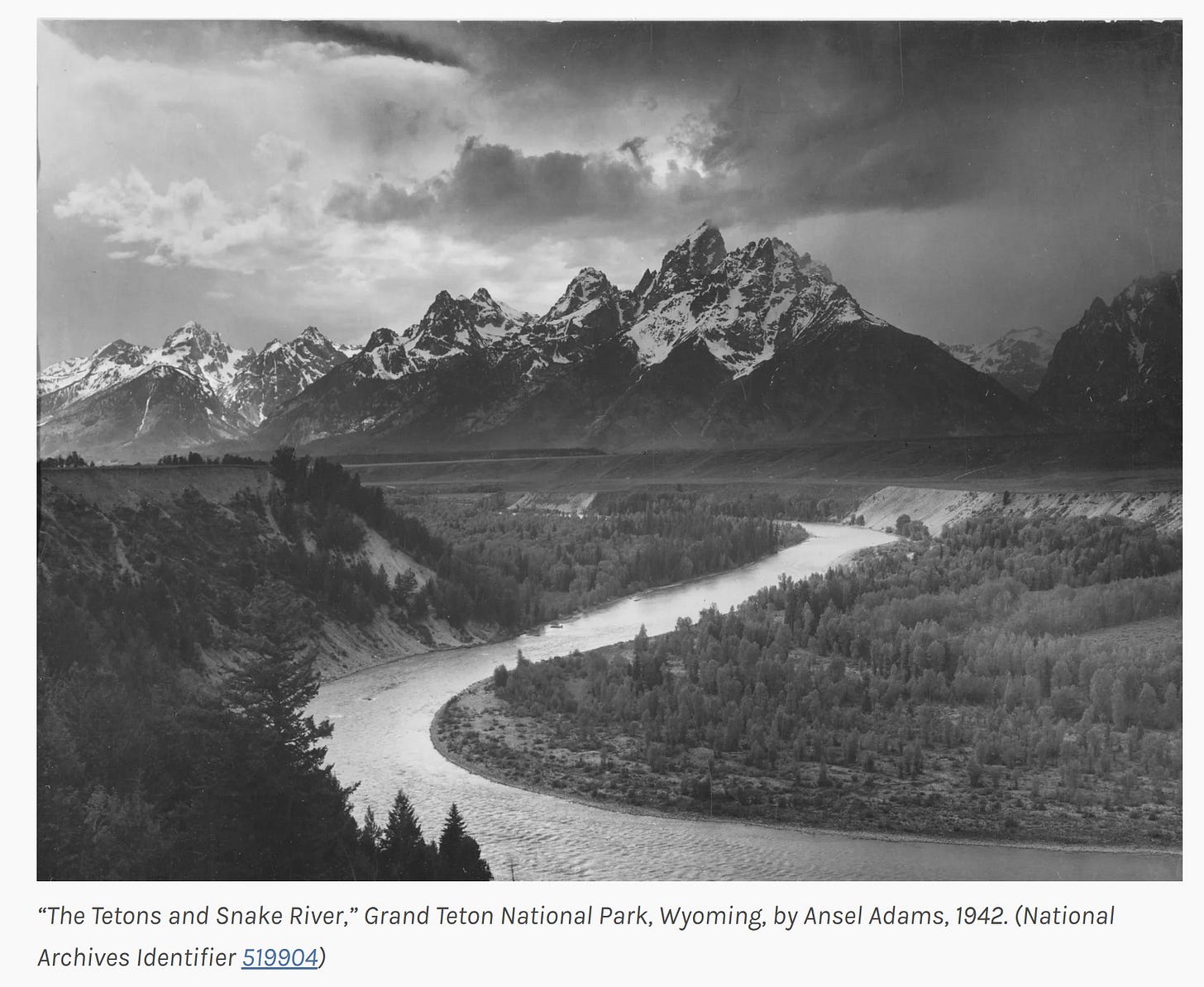

Photographer Ansel Adams, working at much the same time, would say something of the same thing, although not going as far as Anderson: “There are no forms in nature,” Adams wrote. “Nature is a vast, chaotic collection of shapes. You as an artist create configurations out of chaos.” Yet Adams was discussing compositional elements at the time and stopped well short of suggesting an artist somehow completes an otherwise incomplete nature with their work.

It is enticing to think that an artist, or any of us, is somehow vital to the natural world but over the years I’ve come to reject, for the most part, that idea in my own work. I am a witnesses to nature. The connection artists create with the landscape may well bring forth emotions in the other humans who view it but I do not believe that nature itself is gladdened by my work. Nature doesn’t need us, in my view. It is we who need nature, both in a physical and emotional sense. We need to feel like we belong. It is we who reach out to nature, not the other way around. It is we who should be “only too glad” to have that connection with the world around us. It is nature which complete us.

Yet the tools Anderson used in striving to develop a relationship with his surroundings on Horn Island, particularly seeking out direct physical contact, his insistence on solitude, and his detailed observations, were the same tools I have looked to in my desire to know the Apostle Islands. He studied the patterns on the legs of the hermit crab through a magnifying glass, waded eye-deep in the marsh to discover that “a bullrush is just wide enough for a little green frog to get on the other side of and have one eye on each edge, so that he is completely hidden except for his own eyes.” He wrote of, felt, and perhaps most importantly painted, that sense of wonder, surprise, and amazement at those fleeting moments when the seeming chaos of the world around us falls suddenly into alignment like a twist of the kaleidoscope of meaning and insight and we “see.”

Walter Anderson has been called the “John Muir of the Gulf Coast” and the “Henry Thoreau of the South.” I would not go that far, for a myriad of reasons. He was, however, a brilliant, troubled, self-absorbed, and fiercely-independent artist who, at great cost to himself and others, passionately pursued his vision. In his little rowboat and on his wild island, he caught glimpses of the kind of a sense of place that few of us ever know and pinned them to paper in his paintings, drawings, sketches, and writings. The passion of his pursuit has long inspired my own desire to look closely, think deeply, and build a relationship with my chosen place in the world, these islands. I can never see a Walter Anderson painting or a rowboat on the horizon, without feeling again the sweet pangs of that desire for connection welling up inside me.

It is exactly those pangs that course through me again as I slow the Little Dipper to idle and drift close to my friend in his rowboat for a quick “hello.” Still tangled in thoughts of Walter Anderson and Horn Island, I half expect him to be wearing a fedora, an artist, in a rowboat, among the islands, dreaming.

— Jeff Rennicke (all photography by the author unless otherwise noted)

— To see more of Walter Anderson’s work, visit the website of the Walter Anderson Museum of Art by clicking the button below:

— If you enjoy these essays and are not yet a paid subscriber, please consider supporting the Little Dipper by joining below:

I love this essay. Thank you for introducing a marvelous character. In the NYT today is an excellent article about a Shanty Boat - https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/19/us/louisiana-boats.html?campaign_id=2&emc=edit_th_20250820&instance_id=160884&nl=today%27s-headlines®i_id=27551192&segment_id=204248&user_id=df677009e65a80ff046d9aedfdc120f5

It is important that we see these escapes into the natural world as a reminder that through the chaos of the human world there is still an antidote in Nature that we can all go to for renewal and strength. I wrote about it in today's substack https://open.substack.com/pub/mikelink45/p/what-is-my-compass?r=7vnln&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

as another of my favorites - Doug Wood inspired me with his essay.

I am delighted to have you and Doug providing such great inspiration.

Thanks, Jeff. I'm grateful for the exposure to Walter Anderson and the details surrounding his adventures.