Keeper’s Log: Sand Island, May 17, 1991. 57 degrees F. Clear skies. Wind NE 12-15 knots with gusts to 30. Seas 3-5 feet. Ship traffic: no vessels in sight. Visitor count: 0 for the third day in a row.”

For a few days in the spring many years ago, David Snyder (then the historian at the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore) dubbed me the “unofficial keeper” of the Sand Island Light. The job came with slim duties. Automated, the beacon that was once lit by a keeper who trudged twice a day up the 44 steps to the top of the tower, was now triggered by a timing device connected to solar-powered batteries, going on automatically at dusk and turning off just as automatically at dawn. The whole thing was wired, compact, and nearly maintenance free. No coal to haul for any foghorn, no wick to trim, no brass fittings to polish, the best thing I could do was to keep my feet from getting tangled in the cords.

I was there more as the self-appointed inspector of sunsets, for a bit of solitude in which to read and write. And, I was there because a dream is dying.

For most of us, visits to national parks and lakeshores are short affairs, postcard moments. A recent survey showed that 54 percent of all visits to public recreaion areas lasted less than six hours, 80 percent not more than one day. We come, we see, we go home.

Once there were those who lived the wilderness life - trappers, mountain men, prospectors, and pathfinders. There were fire towers where solitary eyes scanned the wild horizons for signs of smoke, pioneer women whose dreams were the size of the blue-domed prairie skies.

But, the hills have been trapped out. Paths found. Firetowers are fitted with video cameras or abandoned. Now, even lighthouse keepers are becoming an endangered species. The dream of a wilderness life is fading, and with it the kind of hard-earned, long-lived intimacy with a landscape that is unknownable to weekend visitors.

Built in 1881, the Sand Island light is one of a string of nine lights within the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore (more lighthouses than any other unit of the National Park Service in the entire country). There is the red-eyed Devils Island Light, Raspberry Island Light with its flower gardens and croquet sets, Outer Island where the 90-foot brick tower is known to vibrate in the storms.

But to me, the Sand Island Light has long been the most beautiful of the constellation. Constructed in the Norman Gothic style using native sandstone, the lighthouse seems to rise right out of the cliffs at the northern end of the island, the views from the tower so vast that the horizon of Minnesota’s northshore some 30 miles distant, is just a dim blue line.

In all its functioning years, the Sand Island Light had only two primary keepers — Charles Lederle from 1881 to 1891 and Emmanuel Luick from 1892 to 1920. The life of a keeper revolved around the needs of the lamp. Each night nearing dusk, they would climb the tower carrying a “lucerne” (a small lantern used to light the main beam). The curtains would be removed, the light uncovered. And then at exactly a half-hour before sunset, the wick would be lit and adjusted to a clear, smokeless flame producing a fixed white beam magnified by a fourth-order Fresnel lens and visible 9 nautical miles out.

Four hour shifts were traded with an assistant keeper throughout the night, trimming and adjusting the wick, cleaning the glass, all to ensure a clear, constant light, a lifeline for the ships passing unseen in the darkness.

A half-hour after sunrise, the light would be extinguished, cleaned, the lamps filled and polished, everything set into place for the next night.

It was honest, simple, yet lifesaving work, often done in outposts set away from towns and the stimulations of civilzation. “Live around these isolated lighthouse stations long enough” said the dejected keeper of another light, “and you’ll be seeing mermaids on the rocks and hear them singing.” To break the strain of that solitude, keepers did what they could to fill their days: the Raspberry and Michigan Island light both had well-tended gardens, the Lighthouse Board began a program of portable libraries that circulated among the lighthouses with titles such as Newcomb’s Astronomy and an eight-volume set of The Library of Choice Literature. Emmanual Luick took up photography.

It could be monotonous but then at times that monotony could shatter like glass.

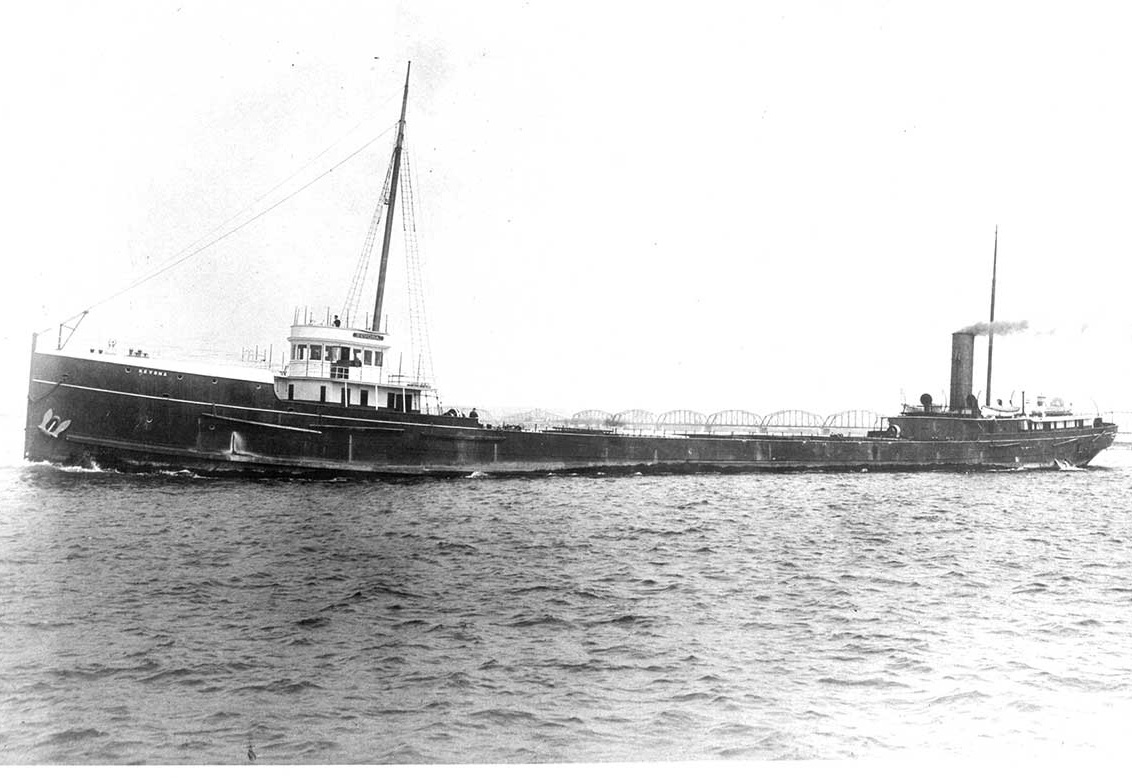

Photo by WHS, Maritime Preservation and Archaeology Program

On the night of September 2, 1905 Emmanuel Luick reported hearing a distress signal from out of the fog as the 373-foot steamer Sevona loaded with 6,000 tons of iron ore and a handful of late-season passengers, was running near Sand Island in a raging northeastern gale. Miscalculating his position, the captain ran the ship bow first on to a shoal between Sand and York Islands. Moments after the crash, too late to be anything but an ironic footnote, the crew reported seeing the Sand Island light.

Two lifeboats filled with passangers set off for safety but were soon lost from view in the fog. The captain and crew, cut off from the lifeboats when the ship broke in half, held on as long as they could and then abandoned the sinkning vessel on a makeshift raft of hatchcovers. Luick could only watch from shore as the seven frantic men fought wave after wave and then vanished beneath the roiled waters.

The keeper’s log for the following days keeps a grim tally as, one-by-one, the victims washed ashore.

Nine decades later, I sat alone in the same tower, looking out over the same stretch of lake. The storm was gone. Automated in 1921, the era of keepers like Emmanuel Luick at the Sand Island Light was also gone. It may seem like a small passing in the scope of things but it is another example of the continuing human distancing from nature. Watch keepers, prospectors, trappers, hermits, even lighthouse keepers, we are losing the knowledge of what it means to live a wilderness life. A light inside of us, unkept, is going to darkness.

Up in the tower scanning the blue where just a single gull flew in seemingly aimless circles, I used my days as the volunteer keeper to try and imagine even a glimmer of that wilderness life surrounded by a silence as beautiful and unbroken as the lake view. Can we truly know a landscape when all we do is peek at it now and again through the blinds of civilization? Can we ever know its true joys and challenges?

On my last day, I climbed the tower for a final time and reached beside me for my spiral bound notebook, the unofficial Sand Island Light Keeper’s log. There I made a final entry as the day and my time at the light began to fade:

“Sky cloudless. Wind NE at 5 knots. Waves 1 to 2 feet. Visitors: none. Ships spotted: two. Mermaids: not yet but I’ve got my eyes peeled.”

— Jeff Rennicke (all photography by the author unless otherwise noted).

Love this piece! It says a great deal of what I have been feeling for many years about our vanishing wildness.

Great story to honor the history of this beautiful lighthouse. Hard to imagine the life of the keepers.