Smoke on the Water

This week in the Apostle Islands, every breath we take should be a burning reminder of just how connected the world really is

I hadn’t planned on writing a blog about wildfires and climate change. In fact, I had a once-in-a-lifetime wildlife experience on Friday that I had planned to use as the topic for this week’s post but more on that another time. No, I hadn’t planned on writing at all about fire plumes and “code purple” air quality warnings but then I also hadn’t planned on getting up at 3am, boating out to Quiet Cove to photograph the sunrise only to find it cloaked in a gray shroud of smoke either. I’m sure that the people in Minneapolis didn’t plan on having the worst air quality in the nation recently and the highest particulate matter readings on their air quality index since the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency began keeping records nearly 50 years ago. I hadn’t planned on seeing that Wisconsin had “the worst air quality on the planet” yesterday. Like hundreds of thousands of others, I hadn’t planned on the sore throats, headaches, and stinging eyes that come from all that smoke either.

Sometimes, the world has other plans and priorities even if all you want to do is photograph an Apostle Islands sunrise.

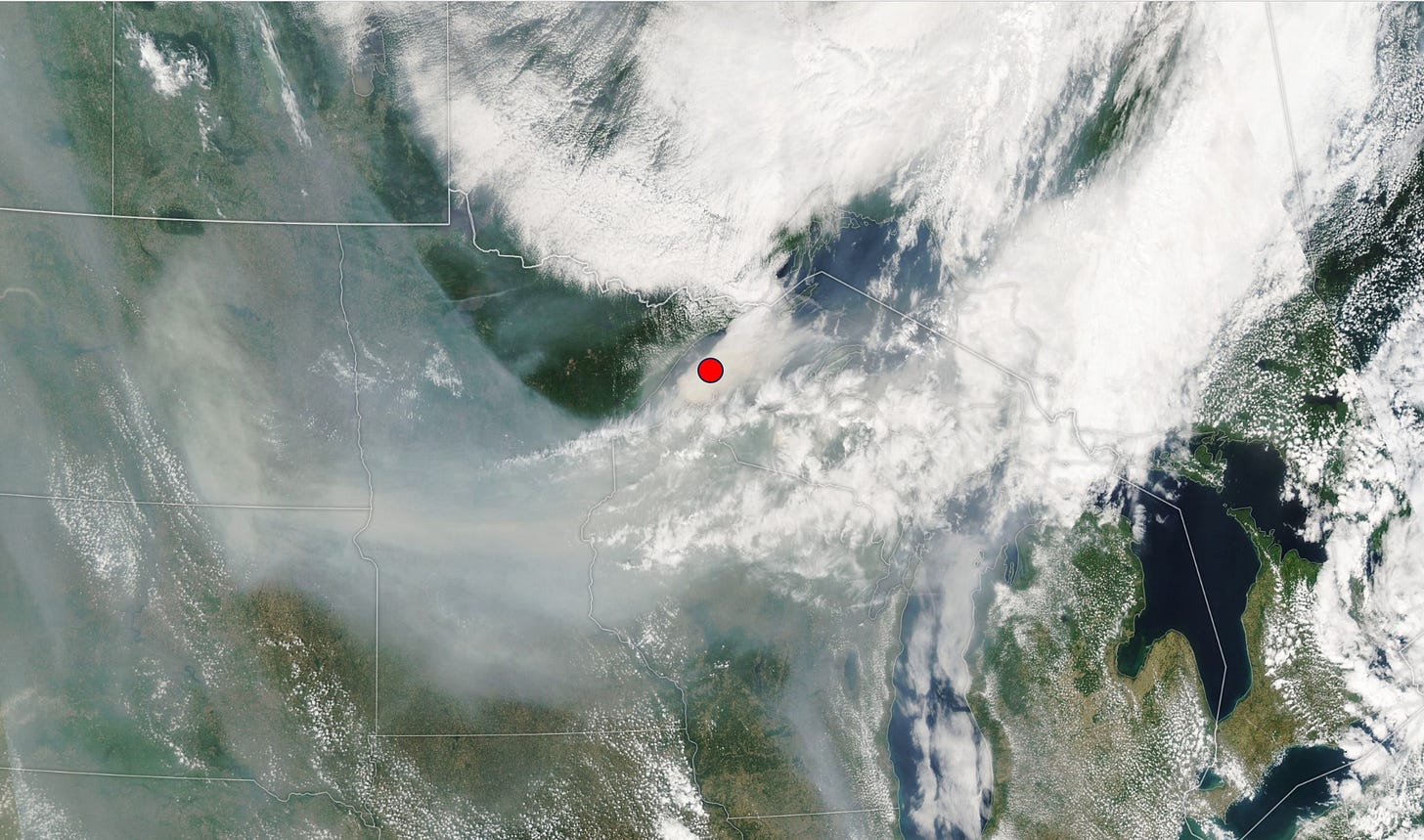

If you would have been with me on the Little Dipper on Saturday morning at 3 am, you would have been somewhere under the red dot in the image above created by a NASA satellite using MODIS or Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer. That is a fancy of way of saying, you would have seen the smudge on the horizon where the sunrise should have been, the wrath of the over 400 wildfires that are burning across Canada, at least half of them still classified as “out of control” as of this writing. You would have seen the smoke on the water where the beauty used to be, and perhaps, just perhaps, you would have seen it all as a warning.

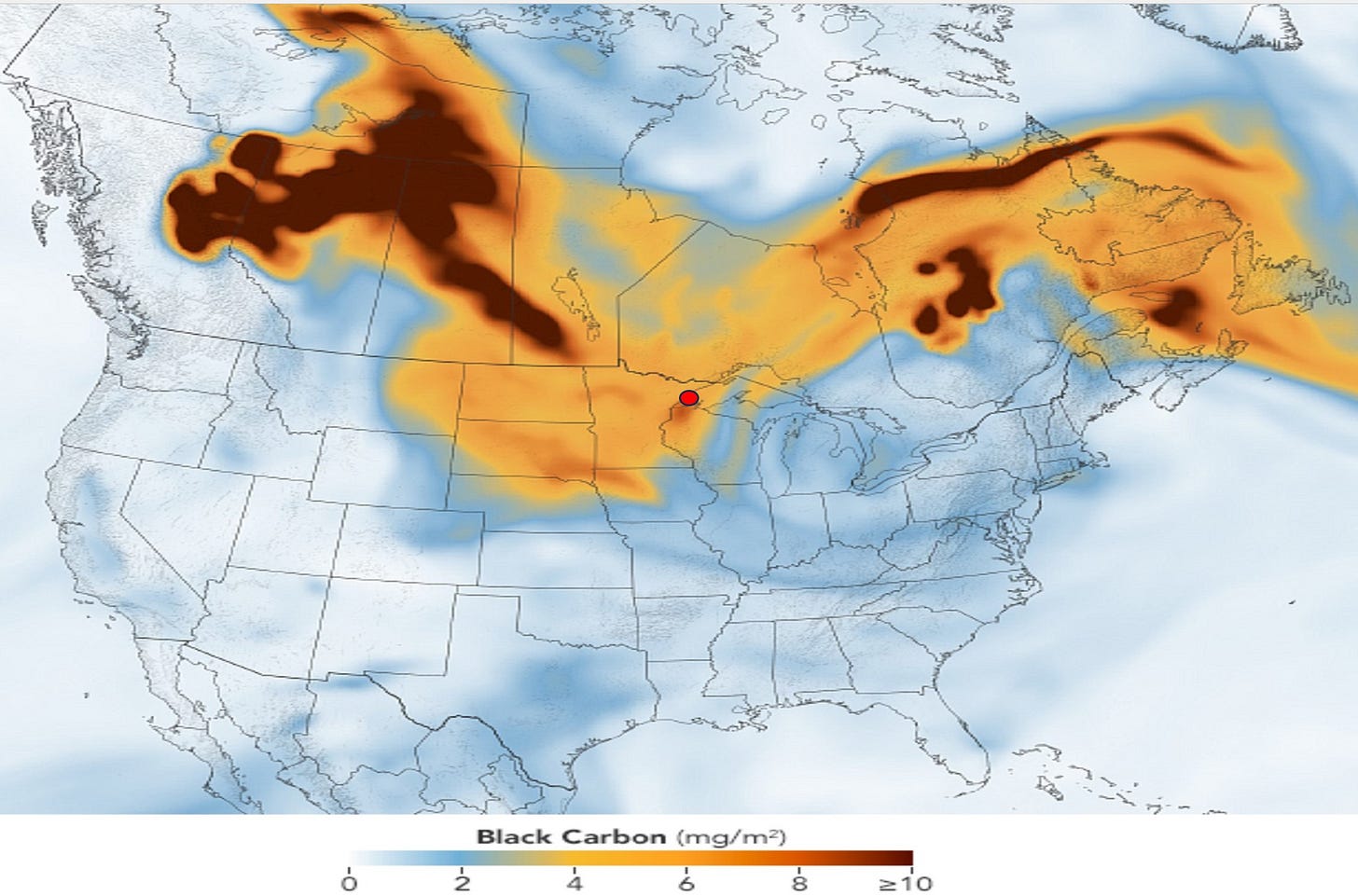

From another image (above) created by NASA’s modelling of data from a variety of satellite observations, the density of the black carbon particulate matter in various parts of the plume from those wildfires and their extensive, almost frightening reach, become obvious. The red dot (again) is approximately where the Little Dipper was on Saturday morning. We weren’t under the worst of it but it was high enough in density to burn your throat, make your eyes sting, and give you a headache as the fine particles blowing in the wind were breathed into your lungs and swirled into your bloodstream.

It was bad in Quiet Cove but even worse in western Canada. The air that day in western Alberta was “code purple” or “very unhealthy” on the Air Quality Index (AQI) scale. We don’t have a lot of Air Quality reading sites in the Apostle Islands but we didn’t need them to know how bad it was. On the Little Dipper scale it made for an eerily drab morning, the islands blanched of all their color but one - gray.

Of course, a colorless sunrise to photograph is a trivial thing compared to the health effects posed by these wildfires and their smoke plumes for millions of people across Canada and the northern United States. Cities like Washington D.C. saw the first-ever “Code Purple” air quality rating in their history. With the plumes of smoke billowing across the upper part of the Midwest and Northeast, our country endured its worst wildfire-related smoke event since at least 2006 (the beginning of record-keeping on such events). It is estimated that 61.8 million people were exposed to unhealthy levels of particulate matter in the air (+50 micrograms per cubic meter) a number that is two times the reach of the second-worst wildfire-related smoke event on the list, one that occurred on September 13, 2020.

And those numbers do not take into account the statistics concerning the people north of the U.S./Canada border which included some of the hardest hit areas. For instance, air quality in a number of cities in Alberta, Canada was ranked as a “very high risk” by Canada’s Air Quality Health Index. And the prognosis is not good. Record heat and dry conditions are likely to continue in parts of Canada, meteorologists say. In addition to the fires already burning in Alberta and Saskatchewan, and those in the east in Quebec, new blazes have erupted in Ontario, almost directly north of the Apostle Islands and Quiet Cove meaning new plumes of wildfire smoke may be on the way as well. Some are saying the smoke may not clear completely all summer long.

The fact that the United States and Canada keep separate numbers on such things points to what may be at least part of the problem: a lack of understanding or an unwillingness to admit that environmental issues like wildfire smoke and climate change are no respecters of international boundaries. As I sat aboard the Little Dipper that morning floating in the grayness and breathing in smoke from wildfires in another country and hundreds of miles away, it became a morning to think not about the beauty of the islands but about their fragility and a reminder of a simple, yet profound truth: like it or not, everything is tied to everything else. Even islands are not cut off from the threads of threats. We are all connected.

Climate experts believe that what we are experiencing this summer may become the new normal. As the Earth continues to warm, what is happening now in Canada will become a regular occurrence rather than an anomaly. The fires in British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan had by just May 16th already consumed ten times the acreage that is normally lost to wildfire in those provinces by this time in the “wildfire season.”

Soaring temperatures, drought and stronger winds are spawning wildfires that burn faster and stronger than they have historically. In the new normal the idea of a wildfire season may become outdated with the potential for fires ranging year-around. The fires themselves will grow bigger, stronger, less controllable. The intense heat will push the smoke columns higher into the atmosphere catching stronger winds and therefore traveling even greater distances. To Quiet Cove and beyond.

Once perhaps I thought I could blissfully ignore wildfires in the American West or in an entirely different country as something that only happens “over there.” I could read about them in the morning news feeds, shake my head in consternation, and then shrug it off as I slipped the lines at the marina and steered the Little Dipper up the West Channel and into the islands where, surely, such things could never reach. I could ignore it all and just write about wildlife and northern lights and beauty. Then I took a breath.

Every breath this week, each photograph of yet another red rubber ball sunrise, should make it painfully obvious that climate change-fueled wildfires and their effects will go well beyond the boundaries of the lands scorched by the flames. Where there’s fire, there’s smoke and while the flames themselves may not reach Quiet Cove or the Great Lakes, the smoke will, and it already is.

As such episodes become more and more common, some experts predict a litany of ill effects to human health for all who live and breathe and boat beneath the plumes. One health expert advised that people “forgo outdoor activity” in response to the wildfires and the resulting smoke. What kind of life will it be when we can no longer hike or paddle? When I can no longer steer the Little Dipper into the islands with nothing more than a search for beauty on my mind?

But, we can no longer look away. Like it or not, we are all connected, a lesson we should be learning this summer with every breath we take.

— Jeff Rennicke

One of the things I have been missing the most, due to the smoke, is the summer luxury of sleeping with the windows open.