A Tally of Ice

Economic stability, biodiversity, and environmental integrity are all at risk with global climate change. But so too, is the simple beauty of ice.

It is one of the greatest opening lines in all of literature. “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad,” writes Gabriel García Márquez at the start of his sweeping novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, “Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

Even without a firing squad, I am remembering ice on this eerily warm December day watching a steady rain melt what little had accumulated managing to at least make it a “White Christmas” this year and wondering what will happen when we lose our ability to “discover ice.”

We hear much these days about the effects of global climate change on the economy, the way changing weather patterns are influencing shifts in population demographics, threatening infrastructure, lessening the biodiversity of ecosystems. And we should. These are all vital conversations to have and topics to research.

Allow me to raise another: a potential loss of ice and its beauty.

For many of us living up here along the south shore of Lake Superior, it has become almost a season unto itself: ice season. You see it beginning tentatively along the edges of the protected backwaters. Ice as thin as wishes and as fragile as stained glass.

Then, overnight it seems to grow, shushing the smaller lakes with the white finger of ice cover and creating another miracle: ice skating. The word spreads that Bark Bay or the Little Sand Bay lagoon is “skateable.” You stop whatever you are doing, dig out the skates, fill a thermos with hot chocolate, wind a scarf around your neck and go because you know it is a snowflake kind of a moment - beautiful but fleeting and likely to be gone too soon. So, chores, appointments, homework, everything else will have to wait. You are going skating.

Slowly, the big lake itself begins to freeze. Ice fishermen appear, hopes rise for the Ice Road allowing cars to cross back and forth between the mainland and Madeline Island. Skiers venture to Basswood Island or Oak. One year, an enterprising group of mountain bikers porcupined their bike tires with studs and peddled to every one of the Apostle Islands across a sheet of clear, stable, and miracle-like ice and changed the National Park Service “Paddling the Apostles” brochure to “Peddling the Apostles.”

And the big one: someone has been out at the ice caves. Long before the National Park Service had an ice protocol and parameters of thickness and stability that must be met before “officially” opening the ice caves, there was just the local word on the street. Someone would go out to check and come back to say, “yeah, seemed ok” and, we’d go. No long lines of people, no parking fees or media. Just knots of locals, bundled up with a picnic, and the kids. The kind of memories that decorate the souls of an entire generation of people who grew up along the south shore of Lake Superior.

But then the winds come to rile it all up. Big ice shoves appear, untold tons of ice tossed like plate glass windows along the shoreline. Huge mountains and ridgelines of ice that seem almost like living things the way they clatter and crash in a kind of winter crescendo. Word spreads at the post office or the transfer station, or just among chance meetings on the street: the ice is in at Bayview or Allen Road or Meyers Beach, or some other spot and you set off immediately to witness the power and beauty of literally mountains of ice to play on.

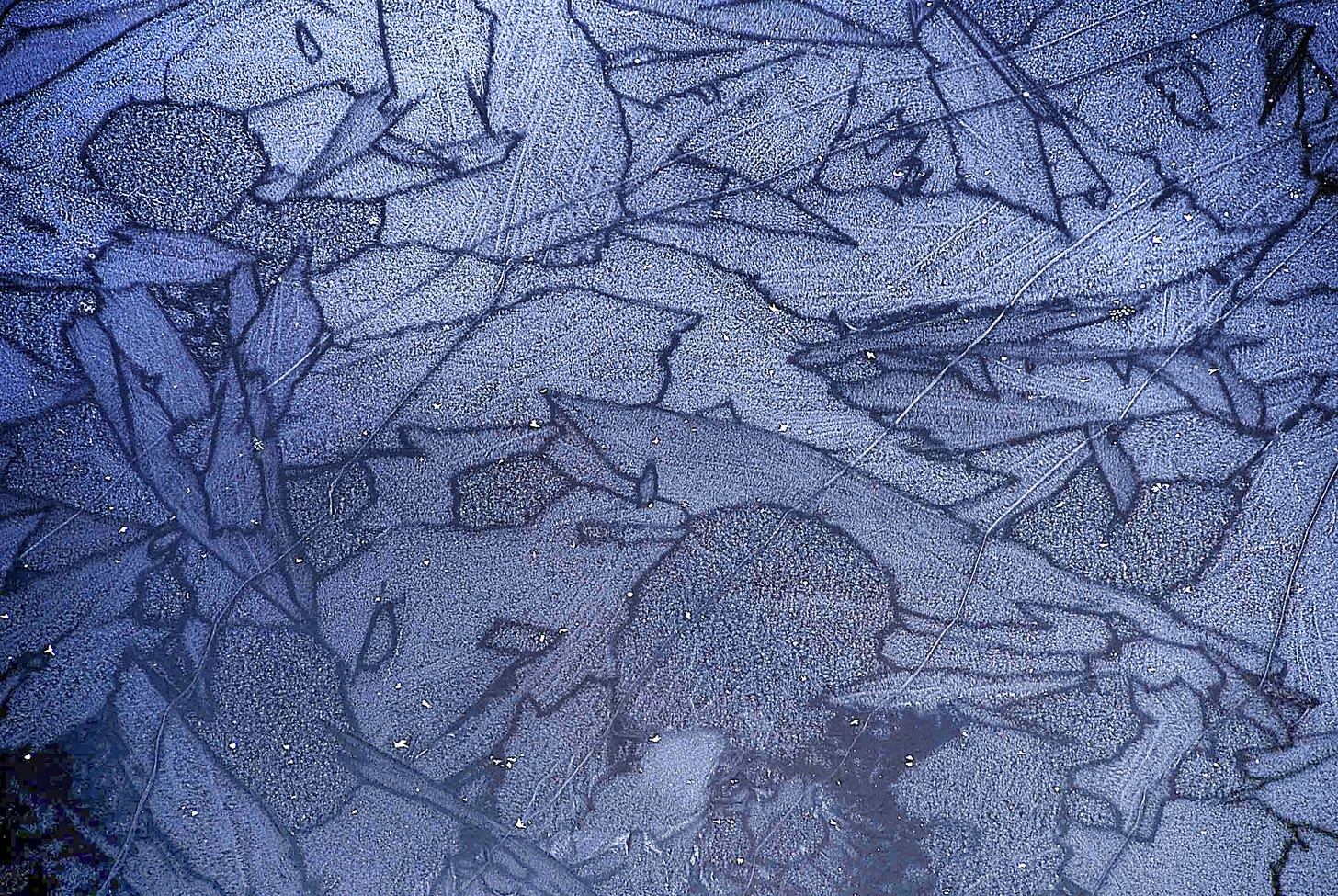

Aside from those epic bike trips and skating moments and the ice castles of the caves, there is a simple wonder to ice. Just water caught in a moment of beauty. What a world to live in where something as simple as clear water and cold air can create such intricate beauty, so fragile you hold your breath when looking at it for fear even the touch of your gaze could melt it away. Along a shoreline, a thin piece of ice becomes a kaleidoscope of color as the waves flicker in and out and the sun twists through its evening palette.

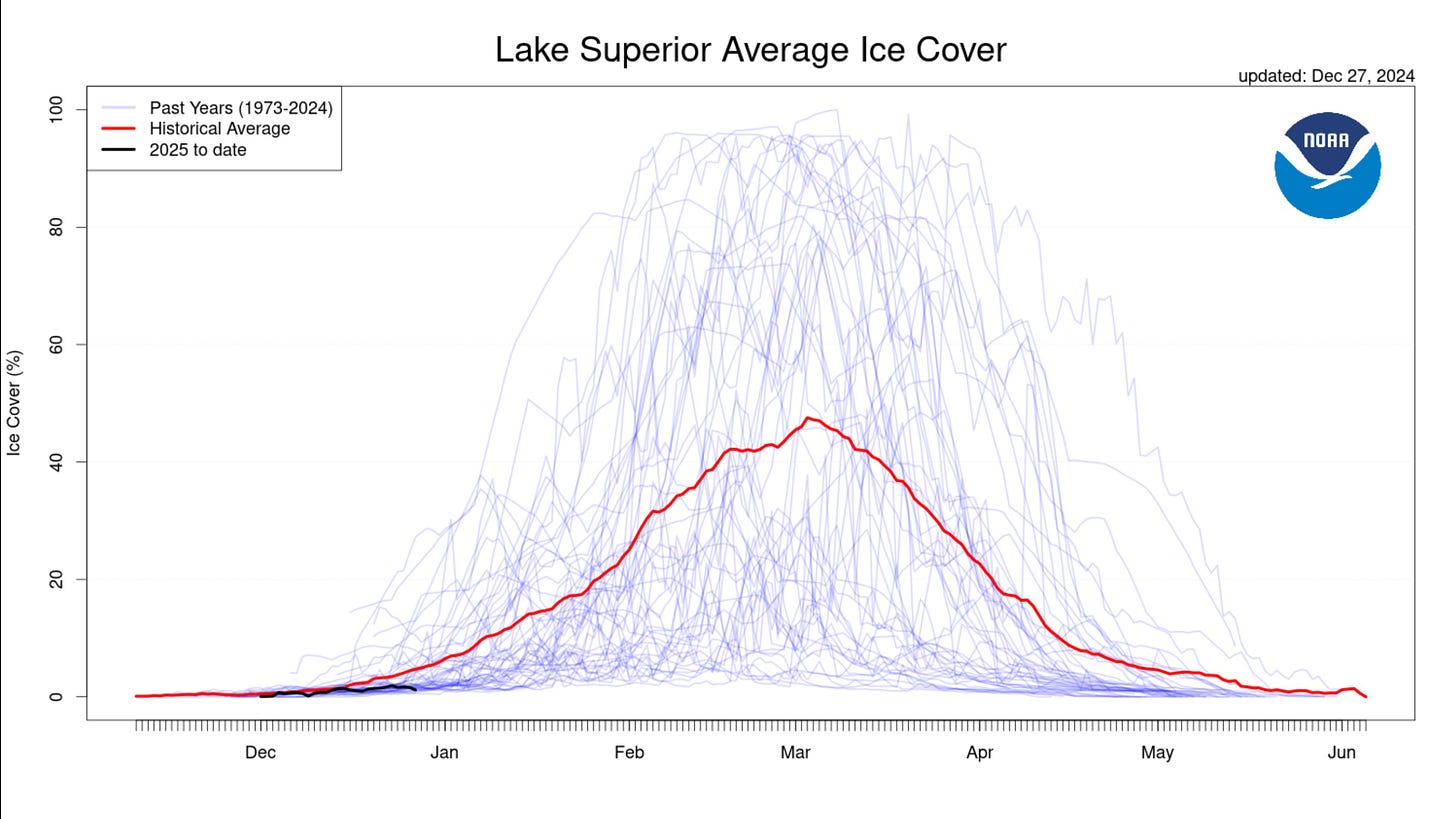

None of that is likely to happen this winter. Coming off of one of the warmest Novembers in recorded history and with Lake Superior ice coverage well below historical averages, there is little or no ice to “discover” along the south shore on this gloomy December day, no post office conversations about ice skating or the caves.

Who will count the cost when all of that is lost to ever-warming temperatures? As scientists tally up the environmental price of warming winters, as economists add up the columns of stabilizing infrastructure against rising sea levels, and biologists subtract the loss of species from the biodiversity of our planet, there should also be painters and poets, skaters and picnickers and children perhaps, to add to the equation. Much more than just dollars and cents will be lost to the world when the last winter has melted to memory. We will lose something of ourselves, our connection to this place and our sense of a shared experience with winters past. There too, should be an accounting of aesthetics. But then, how do you tally something like the opportunity to “discover” the simple beauty of ice?

— Jeff Rennicke (all photography by the author unless otherwise noted)

What are your memories of the ice? Drop me a note below and let me know.