The Two Johnnies (part one of three)

What can an expedition that set sail 125 years ago in a place thousands of miles away teach us about a sense of place in the Apostle Islands? Hmm, this is going to take a while.

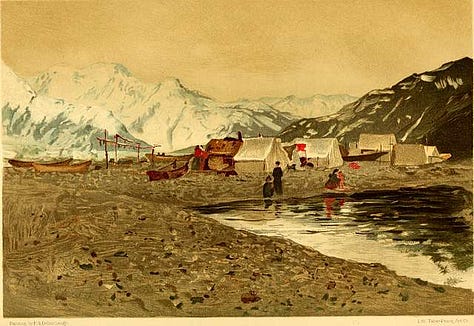

The good ship George W. Elder (photograph by Edward Henry Harriman, 1899)

At precisely 6:00 pm on May 31, 1899, the George W. Elder gave a blast of her whistle and slipped the hold of a Seattle dock. Bands played. Hats were tossed. Crowds cheered.

The 250-foot good ship Elder, owned by E.H. Harriman, the wealthiest man in America, sported dazzling staterooms, scientific laboratories, a theater, a 500-volume library, and a grand piano. Chandeliers swung in its hallways. Champagne flowed in thin-fluted crystal. This particular voyage (known as H.A.E. or the Harriman Alaska Expedition) would span 9,000 miles, last two months, and touch on three countries on two continents. Its departure was the social event of the season for the Seattle elite.

No one knows for sure what Harriman’s true motives were for organizing and financing the H.A.E. Some historians suspect that the railroad tycoon went north with an eye towards profiting from Alaska’s rich natural resources. Some suspect he was scouting a route for a railroad that would encircle the globe with a bridge across the Bering Strait. Perhaps it was to exploit timber or gold or both. One historian even claimed Harriman planned to buy Alaska.

As usual, the man himself kept his cards close to the breast pocket of his well-tailored suit, saying only that the outing was to be “a summer cruise for the pleasure and recreation of my family and a few friends."

Those “few friends” however, were no casual acquaintances. The ship’s manifest counted among its 51 passengers (and 76 crew members) an array of the country’s brightest physical scientists -- mammologist C. Hart Merriam, geographer Henry Gannett, paleontologist William Dahl, and a dozen other botanists and geologists.

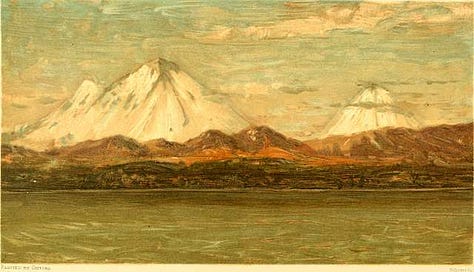

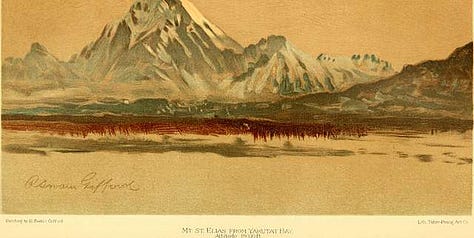

Of a more artistic bent, were landscape painters R. Swain Gifford and Frederick S. Dellenbaugh, and bird artist Louis Fuertes. There was a young photographer named Edward Curtis. Combined these luminaries would help put Alaska, only 32 years a state on the scientific and artistic maps.

The distinguished passenger list made the ship, in essence, a “floating university.” And the scientific accomplishments of the expedition, detailed in a thirteen volume final report, include the discovery of a reported 600 species previously unknown to science including nine new species of algae and 240 species of plants, 38 fossil species newly recorded, natural history collections created, and the largest collection of insects and plants ever surveyed in Alaska. The expedition put dozens of names on the geography of Alaskan maps, took 5,000 photographs, “discovered” a new glacier, and scientifically surveyed the Harriman Fiord for the first time. By any standard, the world's scientific and environmental portrait of Alaska was greatly enriched as a result of the 1899 Harriman Alaska Expedition.

And then there were “the two Johnnies.”

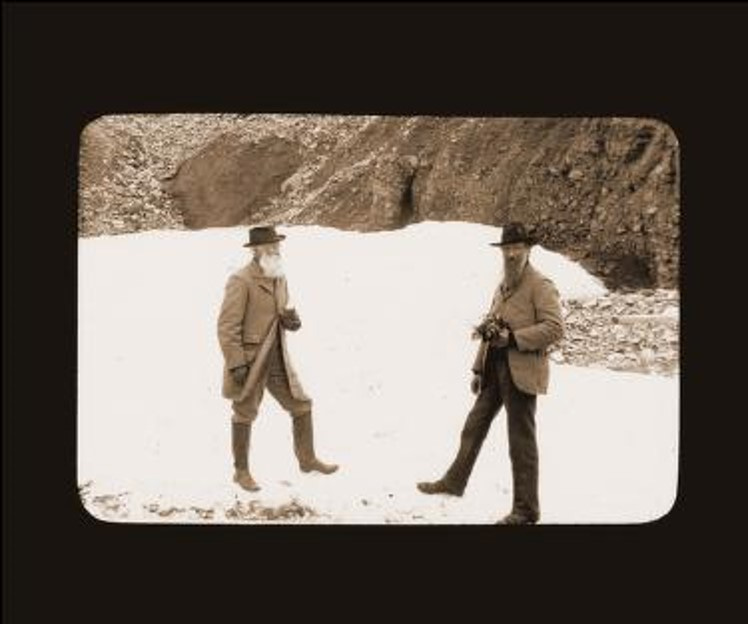

John Burroughs (left) and John Muir (right) on an Alaskan glacier (photograph by Edward Curtis, 1899)

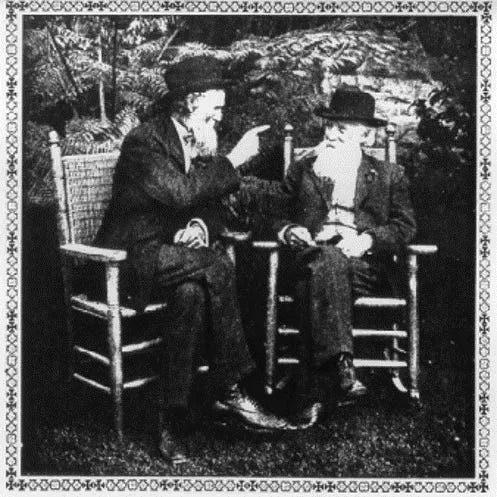

John Burroughs and John Muir were both popular nonfiction nature writers of the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Nearly the same age, both wore long, wispy gray beards. They shared the same first name instantly becoming “the two Johnnies” or “John O’ the Birds” (Burroughs) and “John O’ the Mountains” (Muir) to the other passengers.

Despite the physical similarities, the two writers could not have been more different in personality and, to put it plainly, they did not like each other. At a first meeting a few years earlier each had come away less than impressed. “He had made a speech, eaten a big dinner, and had a headache,” Muir said of Burroughs. “So he seemed tired, and gave no sign of his fine qualities.” As for Burroughs, he called Muir, “A very interesting man; a little prolix at times. You must not be in a hurry, or have any pressing duty, when you start his stream of talk and adventure.”

Once, at a promotional gathering with the two writers at the rim of the Grand Canyon, a guest exclaimed “What luck! The beauty of the Grand Canyon with John Muir thrown in!” Burroughs turned a companion and whispered, “Ay, sometimes I wish Muir would be thrown in!”

Their differences ran deep. It was going to be an interesting trip.

The Little Dipper is no George W. Elder - nary a stateroom or chandelier to be found anywhere. And I am no E.H. Harriman. Still, the philosophies espoused by the two Johnnies, philosophies that clashed so sharply on the 1899 Alaska Harriman Expedition, hover around me each time the Little Dipper slips the lines and clears the break wall and heads for the Apostle Islands. The strange pairing of the “two Johnnies” on the same ship resulted in no great literary accomplishments to rival the expedition’s scientific accolades. Still, the two Johnnies so influenced my own thinking about nature writing that I made the Harriman Expedition (and its literary ramifications) the subject of my Master’s Lecture at Bennington College in pursuit of my M.F.A.

Their ideas concerning the human relationship to nature and their methods for seeking a connection with it, as different as they were, have shaped, and continue to influence, the way I look at exploring a sense of place every trip into the islands. At times, it is almost as if the two bearded sages are right there with me in the tight confines of the Little Dipper, still arguing.

And so, since I am in Alaska for the next few weeks, I will offer, over this and the next two installments of the Little Dipper, a look at the “Two Johnnies,” John Muir and John Burroughs, their writing, their philosophies, and how each one has had such a profound influence on nature literature in America and my own work here in the Apostle Islands. We will see that, as different as they may be, each of their approaches to connecting with nature can help in the search for beauty and meaning in any landscape, even here in the Apostle Islands.

No champagne will be served, in fine crystal glasses, fluted or otherwise, no bands will play, but I hope you will join the journey. It is going to be an interesting trip.

— Jeff Rennicke

— Jeff Rennicke (All photography by the author unless otherwise noted).

Have you been to Alaska following in the footsteps of John Muir and John Burroughs? Use the button below to drop me a note and tell me about it.