I love these islands. There, I’ve said it. And, like all love stories, I can remember exactly the moment it started: two families aboard a sailboat named the Reverie, or more accurately at that moment aboard its dinghy as we ferried our children to shore on Cat Island sandspit to explore the limitless horizons of a July day on hot sands beneath a flotilla of summer clouds. It all fell into place at that moment — the islands, family, adventure, beauty, and home. That is the moment I fell in love with the Apostle Islands.

True love. Not the heart-throb cotton candy love of a pretty sunset or the puppy love of rainbow ribbons and Hallmark cards. I bobbed in that dinghy that moment, watching our kids explode like a flock of barefoot sparrows down the endless beach, waves breaking all around us with the sound of a beating heart, and knew that this was the place that I loved.

It was an awakening, but also a challenge. For with the admission that you truly love some place or someone, comes a question: what does it mean to love?

Love is a word we toss around like glitter these days. We say offhandedly that we “love” a certain food or the latest box office hit or a new song that is currently trending. But, do we really? That movie or song will soon be forgotten in the endless tide of the next latest thing. True love, it seems to me, must have more staying power. It is a bedrock kind of thing, foundational to who we are and our place on earth. It doesn’t fade with the stage lights or the unveiling of the next season’s fashion trends. It is timeless, cast in glass. It sticks.

And, it is, I’ve come to realize more than just a physical, sensual thing, although that is part of it too. I am in love with the way the warm sand caresses my bare feet on a July beach, and the soft sway of beach grass. I love the colors of the rock at sunrise on the sea caves and the color wheel of hues in the sunsets over the open lake. There is that full-on ecstasy of plunging into the lake for the first, or last, swim of the season, and the mesmerizing poetry written in the soft swirls of sea smoke on a winter’s day.

I love the slow ache of its distant horizons, the kind that make you feel both a euphoria about being alive and that tinge of sadness that life is so short. I love the puzzle pieces of the islands at a place like the overlook on Oak Island where you can gaze out at five… six … seven islands at once, a kind of constellation in the sky-blue waters of Lake Superior. There is Stockton Island where the sand “sings” under your feet at Julian Bay and Devils Island with its red-eyed lighthouse. There is the long comma of the Outer Island sandspit where the wind is stirred with wild wings, and the maze of sea caves where the wind plays in the rocks like flute music.

Each sensation deepens my love. But while you can love a place with your body and with all of your senses, there must be more to it than that for the love to be true.

Look closer. To a kayaker moving silently on a day when the fog blurs the edges, or a sailor crossing a reach at sunrise, these islands can seem as wild and remote as the last stars in the evening sky, untouched and untouchable. But they are not. Look deeper. There are stories here. Suddenly, the cribbing of an old dock appears beneath your boat. Hiking a trail you find the bricks of an old chimney toppled in the brush, the shell of an old safe or the curved teeth of a hayrick silent now in the grass. There, on the shore, stacks of cut brownstone awaiting a tug that will never come.

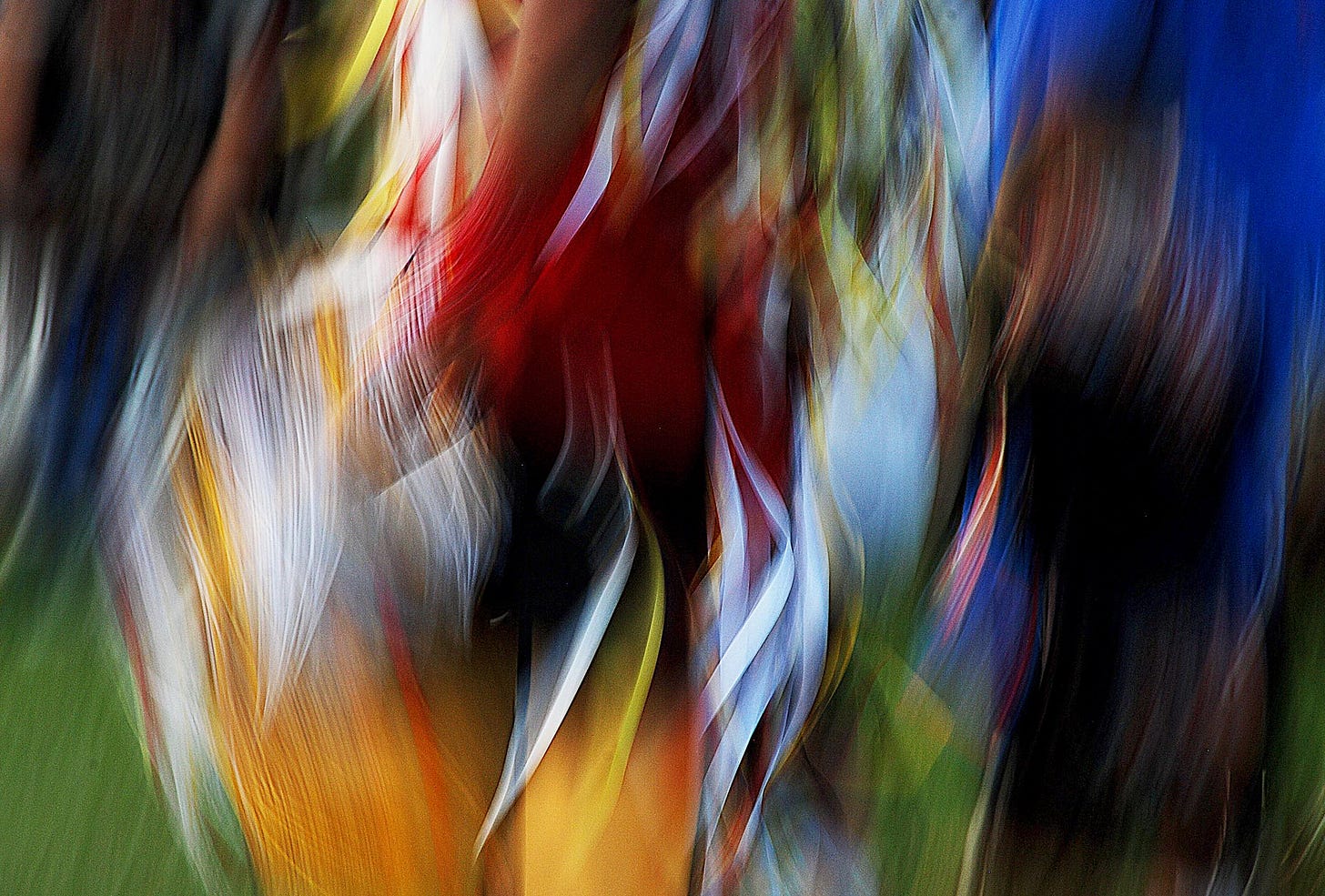

(The swirl of feathers in an Ojibway dancer’s ceremonial dress during a Pow Wow)

There is a long human history woven into the fabric of these islands beginning with the stories of the Ojibway whose roots sink deeper than the white pine into these islands. Voyageurs, loggers, hermits, fishing families, lighthouse keepers, and ship captains. History runs deep here. That history has sometimes left its mark carved deeply into the island bedrock and sometimes left nothing more than a half-remembered campfire tale, but this is, as environmental historian William Cronon has called it, “a storied wilderness.”

Each story becomes a kind of a love story, for me, woven of the threads of place, people, and dreams. And from those hopes and dreams, from that love, rises a kind of strength, the strength to move ahead in uncertain times. “It is more important now to be in love than to be in power,” says author Barry Lopez in his essay Love in a Time of Terror, more important “… to live for the possibilities that lie ahead than to die in despair over what has been lost.”

Much has been lost in the world, in these islands, and much more stands on the crumbling rock of a precarious future. But love, true love, does not allow for giving up, not as long as you can answer “yes” to the question Barry Lopez asks at the end of that same essay: “… is it still possible to face the gathering darkness, and say to the physical Earth, and to all its creatures, including ourselves, fiercely and without embarrassment, I love you …?”

The answer has to be, must be, can only be “Yes.”

— Jeff Rennicke (all photography by the author unless otherwise noted).

Use the button below to tell me why you love the islands or your own chosen landscape.

Stunning, as always. Thank you, Jeff.

your love affair with this place. To the question posed by Barry Lopez, I say Yes!