The Taste of Time

What does a meal of 36,000 year-old steppe bison stew have to do with our understanding of the concept of deep time?

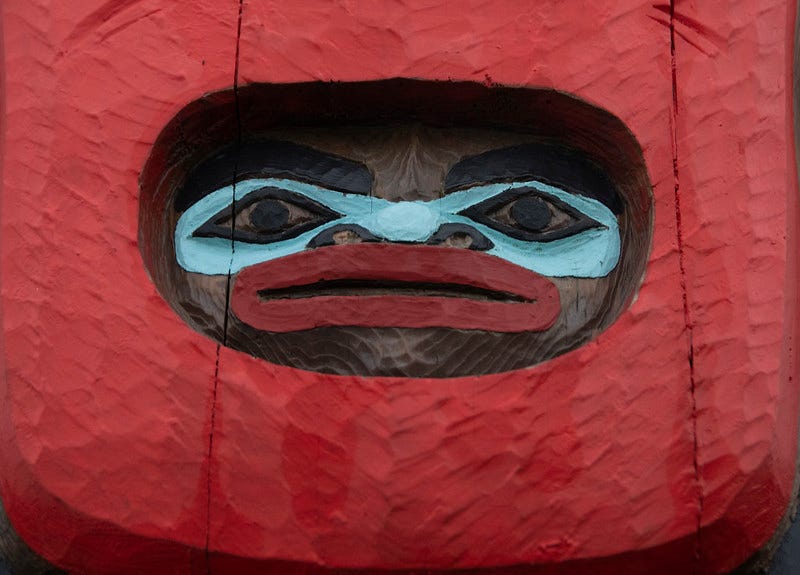

It is impossible to spend a long stretch in Alaska, as I just have, without thinking about the passage of time. It is a land etched with stories of time, from the slow press of glaciers carving claw marks in solid rock to counting the minutes between the spouts of humpbacked whales traveling through the reaches of Chatam Strait and the generations of storytelling carved into a totem pole along the shoreline. This land wears time in its every face.

We can see time in the layers of rock. We can hear its ticking in the slow cadence of whale spouts. But, standing at the edge of Mendenhall Glacier recently, the water strewn with chips of glacial ice, I wondered does anyone know what time “tastes” like? And then I smiled, remembering a story I related in my book Treasures of Alaska: Last Great American Wilderness. It is a story that took place far to the north near Serpentine Hot Springs in the Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, a story of a 36,000 year-old steppe bison, a good bottle of burgundy, and brave man named Dr. Dale Guthrie of the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

In Alaska’s far north, the sun never leaves the sky in summer and doesn’t rise in winter. Off the coast Yupik whale hunters drift back and forth across the International Date Line, technically moving from ‘today’ into ‘tomorrow’ and back again. Time just moves differently here, or so it seems, particularly on the soft gray days when fog and mist shroud the tor-lined ridges of the Serpentine River Valley in Bering Land Bridge National Preserve.

Artifacts from this valley indicate humans lived here at least 6,000 years ago. But for even longer people have been coming to this place to heal, to pray, and to soak in the hot, mineral-rich waters that seem to bubble up from the very soul of the Earth. Shamans came here as entry to sacred worlds and the powers beyond.

At Serpentine Hot Springs today you can still find that sacredness and power. This is a spot where on a foggy day even time itself seems to get tangled in the mist. Ease yourself down into the 140 degree jade green pool and let the rising mist blur your sense of time. Squint your eyes and you might be able to see an early winter day hundreds of centuries ago. Perhaps a bull steppe bison grazes in the green-brown swell of a small river valley. Perhaps a ray of low sunlight almost without warmth touches the top of a distant ridge. The bison looks up once, stops chewing, and then bows its head again to graze.

Before its gray-black muzzle even touches the wind bent grasses, there is a rustling in the brush, a blur of teeth and claws and dust. A sound somewhere between a groan and a bellow gurgles from the bison’s throat and then — 36,000 years later — the phone rings in Dale Guthrie’s office at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks.

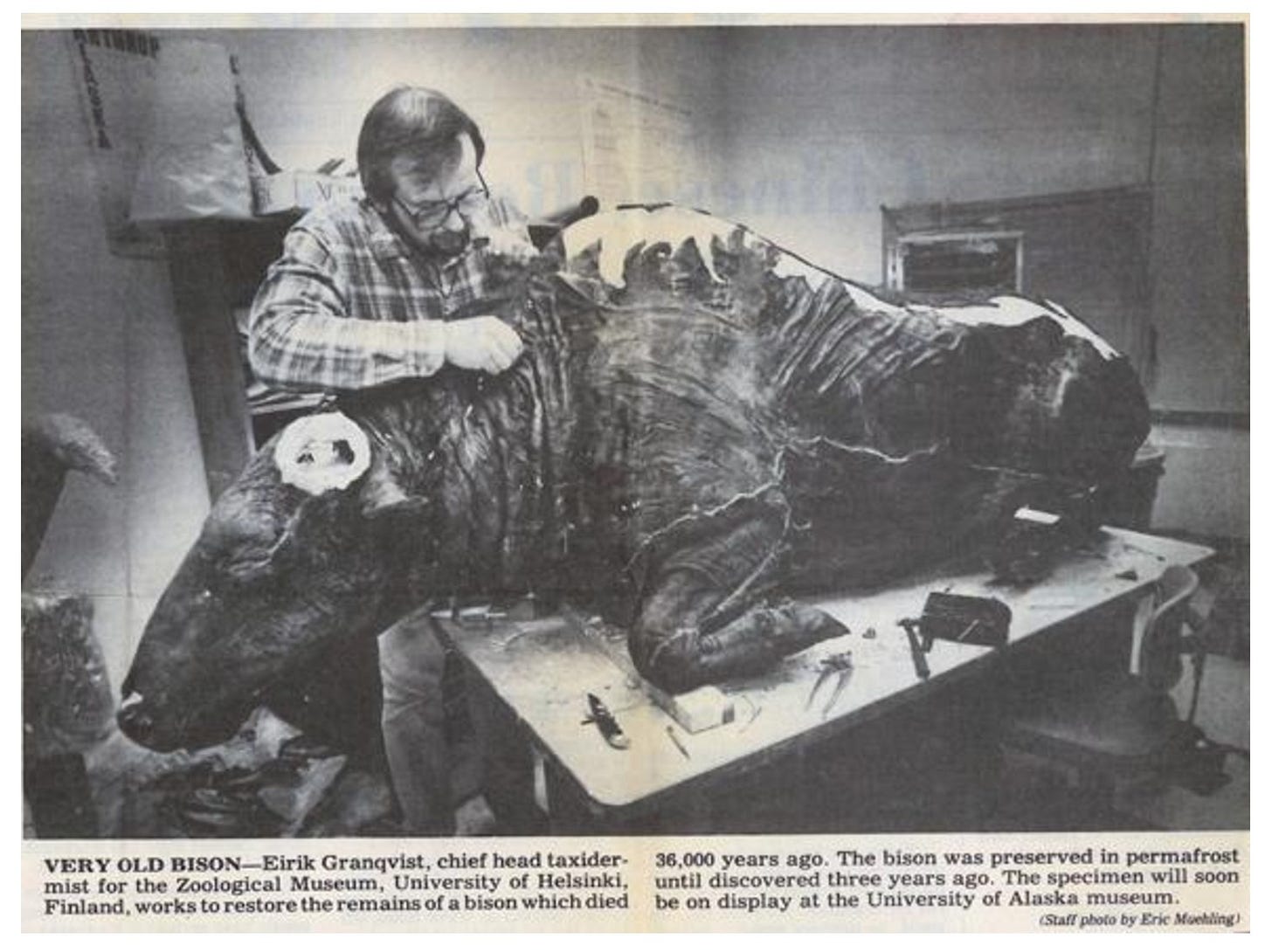

(University of Alaska Fairbanks photograph)

“We received a call from a miner in July of 1997, saying a couple of hooves were sticking our of a silt bank he was working near Fairbanks,” Guthrie tells me. “Although we get reports about mummies all the time, good specimens are exceptionally rare, about one a decade all across the Arctic. In Alaska, it has happened maybe five or six times in the last century.” This one, he says, “turned out to be pretty spectacular.”

Fossils and bones can provide clues to a creature’s anatomy but a nearly intact mummy of a Pleistocene steppe bison was a scientific bonanza allowing researchers to ask a broader range of questions. Hair samples gave clues to environmental trace elements. Complete muscle masses helped flesh out a detailed picture of body shape. Plant fragments trapped in the teeth told of the bison’s diet and revealed what plant types thrived in Alaska so long ago.

Still, there were stories that the mummy didn’t tell, at least not at first. Early in Guthrie’s research on the bison that he dubbed “Blue Babe,” he hypothesized that the animal had died from natural causes and been scavenged by smaller creatures. But scratches and punctures on the carcass nagged at his mind. “I thought, just as a kind of fantasy on the way home one evening, wouldn’t it be interesting if those scratches were lion marks?”

Returning to his lab, he took the skull of an American Lion, a predator that once roamed Alaska and was not unlike modern-day African lions, and placed its large incisor teeth against the marks on “Blue Babe.”

They were a perfect match. Hidden in the hide, a tooth fragment - part of the lion’s carnassial - confirmed the theory: Blue Babe hadn’t died of natural causes, it had been killed by two, possibly three, American lions suggesting a social structure among the predators and teamwork in taking down such big prey.

“The story started to get better and better,” he says. “Instead of just a description of the carcass, we had evidence of how the bison died and what the ecological picture could have been in northern Alaska 36,000 years ago.

(University of Alaska Fairbanks photograph)

Today, Blue Babe rests in a glass case in the University of Alaska Museum, forever caught in the death pose it struck as the lions brought it to its knees. Its original discovery proved to be “a set piece in constructing the way we view the Pleistocene,” Guthrie said. “It was a book thrown through time.

But before he could close the covers on that book, Guthrie hoped to learn one more thing: “I’d grown up hearing about Russian hunters eating steaks from frozen mammoths in the Arctic,” he says with a smile. “No scientist had ever before had the opportunity to prove or disprove those stories.” So Guthrie and his wife scraped a few morsels of red meat from the still frozen bison carcass, gathered a group of brave friends and colleagues, and with “a good bottle of burgundy” sat down to a meal of 36,000 year-old steppe bison stew. All in the name of science of course.

And so how did it taste? I ask one of the only people who might now what time tastes like. “It tasted” Dale Guthrie tells me with a grin, “a little muddy.”

Thinking back on the tale of Dale Guthrie and Blue Babe as I walk along the edge of the Mendenhall Glacier, I came across the remnants of an iceberg broken off from the main glacier like the shard of a fallen star, ice that could have been hundreds or thousands of years old, stuck in the glacier on its long, slow crawl to the lake. It wasn’t 36,000 year-old steppe bison stew, but it was something. So, carefully I tip-toed out through the silt-laden waters, close enough to break off a small piece, my own taste of time, and slipped it on to my tongue.

Working my way back to shore, cold water seeping into my boots, the little piece of ancient ice melting on my tongue, I had to agree. Time, it seems, tastes a “little bit muddy.”

— Jeff Rennicke (all photographs by the author unless otherwise noted).

Great story. Any thoughts on why the lion’s didn’t eat the bison?