(In 1899, both John Muir and John Burroughs joined the E.H. Harriman Alaska Expedition. Despite the differences in their personalities and approaches to nature, Muir and Burroughs each sought the kind of connection with the natural world that many of us are seeking even today. In this three part series, we are exploring the legacy of the “Two Johnnies” and what we can learn from each of them in our own quest for sense of place. To read parts One and Two, click below. Otherwise keep reading for a look at John Burroughs, the Bard of Forgotten Beauty).

It is not a tree stump, the favorite writing spot of John Burroughs, but it will do. My friend Bob Jauch, who delights in these islands as much as I do, joined me for one last trip aboard the Little Dipper, a late season celebration to fill our pockets with the last of autumn’s warmth. We wandered like a spiraling leaf but ended up at the dock on Quarry Bay. He was so anxious to walk the beach and collect the last color like pocketsful of dried leaves to hold him over the monochrome months of winter, that I stayed behind drinking coffee on the dock, letting him have the thin strip of beach to himself. I positioned myself on a camp chair at the end of the dock and stayed put, letting nature come to me, just like John Burroughs used to do.

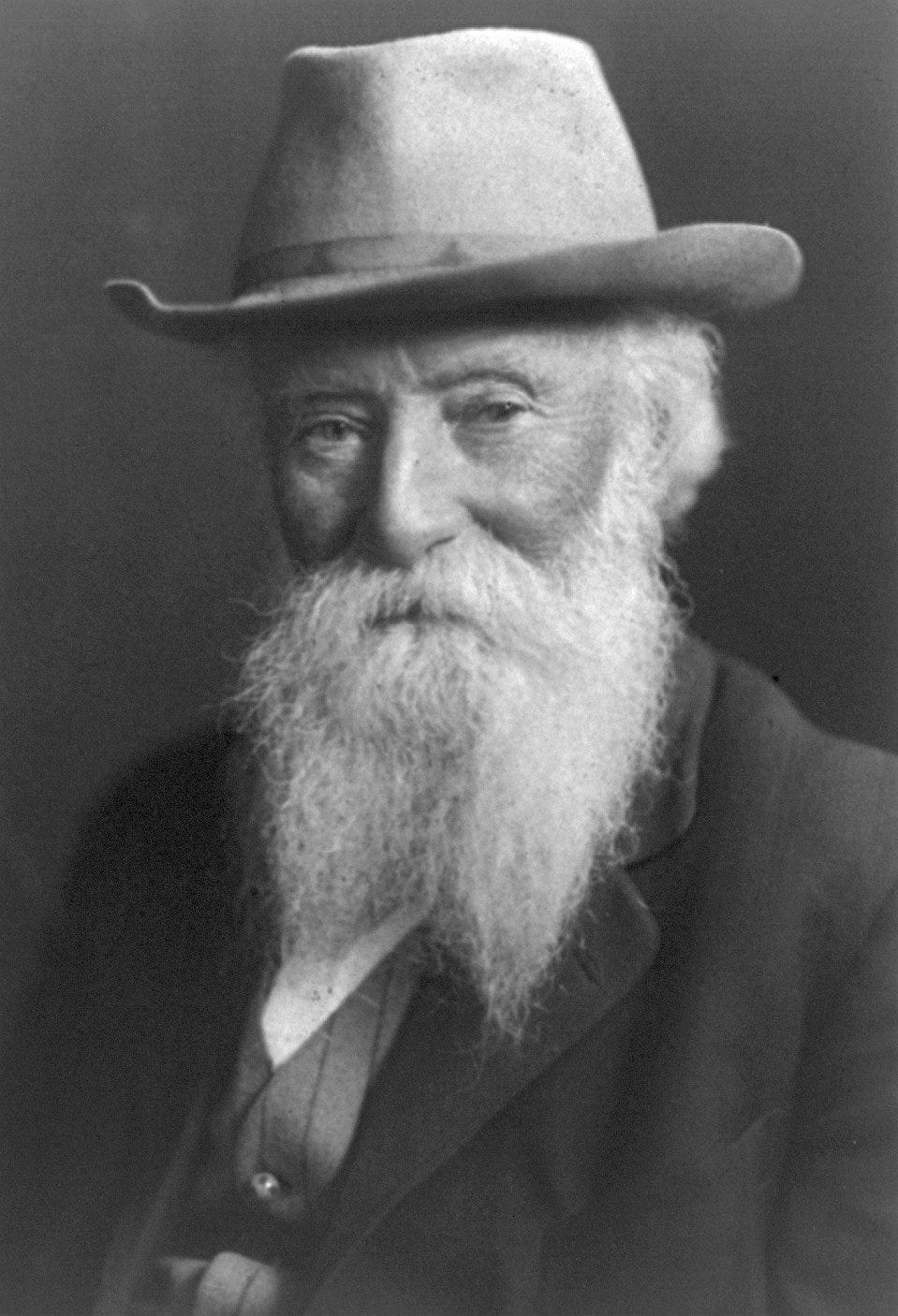

(Library of Congress photograph)

Born in a New York farmhouse in 1837, John Burroughs was a self-described “home-body and lover of the cozy.” He was the bard of the buttoned-down landscapes, disliking tangled, places, he said, “where I might lose my hat.” Unlike the worldly John Muir, for Burroughs the cross-country trip to Seattle to join the E.H. Harriman Alaska Expedition in 1899 was his first venture west of the Mississippi.

“I had no adventures, no hair-breath escapes; and but little to write about,” he admitted. “But you know a writer gets only the seed corn of his article from without. He grows the main crop himself as he writes, at least I do.” Burroughs poured those observations into 25 books becoming one our most beloved literary figures. By the late 1800’s every school child in America grew up reading his essays and Slabsides, his cabin on the Hudson, became a literary shrine drawing Walt Whitman, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Thomas Edison, Teddy Roosevelt and Henry Ford who considered Burroughs work “superior to that of any author who ever lived.”

Burroughs life was a practicum of the pastoral, an ode to the simple art of observation. His genius lay in turning himself into a light sensitive plate exposed to the shining world around him. “Success in observing nature,” he wrote, “depends upon alertness of mind and quickness to take a hint. One’s perception must be like a trap lightly and delicately set; a touch must suffice to spring it.” Nothing was too light a touch to spring the mind of John Burroughs:

Not the plants of the forest floor: “Whatever is upon the earth is of the earth; I never see the spring flowers rising from the mould, or the pond-lilies born of black ooze, that matter does not become transparent and reveal to me the workings of the same celestial power that fashioned the first man from common dust.”

Not even a bird nest: “There is a mist of green over the woods and splashes of white here and there. I know a partridge nest with nine eggs. Come and see what the dry leaves cover!

That last passage is reflective of Burroughs philosophy. It is, first, an invitation – he claimed with pride that the writing of Emerson and Thoreau caused the public to seek them out while his work inspired people walk in the woods. Then, while other writers might look and rejoice in the new growth, the “mist of green” overhead, Burroughs looks down at the old leaves that most of us would ignore. He peels back the layers of the familiar and reveals the miraculous. Look, John Burroughs seems to say, look closer, look again. The possibility of art lies in the familiar, if you keep looking.

“Familiarity with things about one should not dull the edge of curiosity or interest,” he wrote in his essay New Gleanings in Old Fields. “The walk you take today is the walk you should take to-morrow, and the next day, and next. What you miss, you will hit upon next time. If Nature is not at home to-day, call to-morrow, or next week.”

While John Muir chased nature up and down the wild slopes of the world, John Burroughs would often simply sit on a tree stump and let nature come to him, pushing himself to find beauty and meaning in the commonplace and close at hand.

In my own search for a sense of place among the Apostle Islands, I have seen my own desires switch from the Muir-like pursuit of adventure to the quiet, deep observation techniques of John Burroughs, from a rock skipping across the surface of the water to a stone sinking down deep. Or, a leaf.

Back on that dock in Quarry Bay, I was fidgety at first, thinking I might miss nature’s show by just sitting still. Little did I know that I was positioned for a parade. A string of current was running, it seemed, directly from the edge of the beach where the leaves were falling, out passed the end of the dock where I was sitting. A chorus line of autumn leaves pirouetted in that current right at my feet. It was as if I’d found a river of colorful falling stars in a backwater of the night sky. Each one taking its own solo dance against the blue-green water.

It was autumn at a more sane pace, the season simplified. True beauty, it seems to me, lies as much in the details of a single leaf as in the flourish of fall hillsides. I sat sipping coffee, watching the solo dancers passing each in turn spotlighted by a ray of November sun, thinking each one would be the last, a kind of grace note on the season.

They were still passing when Bob came walking back down the dock where we had cleated the Little Dipper. He stood silently a moment, noticing my reverie, and then asked “See any good color?”

“Perfection,” I answered.

We slipped the lines, cleared the dock, and started out of the bay. Just as we pulled away I caught a speck of color and turned to see, on the transom of the Little Dipper, a single red leaf clinging to the edge of the boat. My attention turned to safely getting underway and so I powered up, and brought the Little Dipper up on plane and pointed safely towards home.

When finally I looked again, the leaf was gone. Autumn was over but I had witnessed its passage in a single leaf. Somewhere, somehow, I knew that John Burroughs would be sitting on his tree stump smiling.

— Jeff Rennicke

If you are a paid subscriber to the Little Dipper, thank you. Your support is appreciated. If you are a free reader, I hope you will come to value what you find in these pages enough to upgrade by clicking below:

Do you love the art of observation, the little things? Send me a note using the button below and tell me about it.